Virtualization is a process that allows a computer to share its hardware resources with multiple digitally separated environments. Each virtualized environment runs within its allocated resources, such as memory, processing power, and storage.

– AWS

Preamble

This post is part of a series of articles on project Superphénix (SPX) where we present how we rebuilt the infrastructure of an existing cloud provider from scratch, using cloud native technology and Kubernetes.

If you want to know more about specific topics, check out the other articles and the introduction!

Handling Virtualization in Superphénix

If you’ve read the introduction to project Superphénix, you know that our goal is to rebuild (from scratch) the infrastructure of a Cloud Service Provider (Agora Calycé) using Kubernetes and cloud native technology.

This means handling the virtualization of VMs using Kubernetes as the VM orchestrator. What we want is to make VMs as simple as containers or pods.

But why? Kubernetes is a container orchestrator. It doesn’t know how to handle VMs natively.

The reason is simple: we live and breathe Kubernetes and we want to inherit its benefits.

The expertise of Agora Calycé in Kubernetes and its orchestration has facilitated the streamlining of their daily operations. However, our ambition extended beyond the mere provision of containers on our infrastructure.

We think there’s potential that exists to expand the orchestration functionalities of Kubernetes on virtual machines (VMs). This is due to the fact that VMs and containers share many similarities. Our goal is not just to deploy VMs on Kubernetes because we feel like it’s a good idea. The goal is also to extend this pratice to all aspects of containers, including monitoring, networking, storage, and automation.

Our ambition is to inherit all of the good aspects of Kubernetes, but to orchestrate VMs instead of containers. Think native metrics, CNI/CSIs applied to VMs, billing through Prometheus, scheduling, taints, affinities, Gitops and more. Concepts that are native to Kubernetes and that we want to use on our virtualization layer. The objective is to reduce the time spend on tasks that Kubernetes can already perform competently.

Kubernetes is incredible at automation, so why not use it?

The Project That Makes It Happen

You may already know we’re using Kubevirt to run VMs alongside containers.

This simple operator installed on a Kubernetes cluster extends its API with new CRDs to create, clone, snapshot, restore and scale VMs. Kubevirt, a project mainly maintained by Red Hat is currently our only hope to achieving our goals. It does exactly what we want and more.

We also use the Container Data Importer which helps us provision and create VMs disks on the fly, using sources such as HTTP servers or Docker containers.

How Does It Work?

When Kubevirt creates a VM, it does not simply create a VM. The system generates a pod that functions as a controller, which is also observable within the Kubernetes environment and serves as an interface.

Specifically, when a VM is requested, Kubevirt launches a pod that will initialize a VM directly on the machine, independent of the Kubernetes cluster. This pod will then act as a continuous link between the cluster and the VM. This pod named “virt-launcher,” oversees and manages the VM in response to requests initiated through Kubernetes. Additionally, it will function as a network gateway between the cluster and the VM.

Because VMs are represented by Pods in the Kubernetes cluster, we can inherit the CNI of the cluster through the network allocated to the pod, and inherit the CSI of the cluster through PVCs bound to the pod.

Why Mixing VMs and Pods is a Good Thing

The utilization of the virt-launcher simplifies the operation of the VM as a pod within the cluster. As far as Kubernetes is concerned, the pod is synonymous with the VM.

This mechanism has the capacity to facilitate the implementation of various services running alongside the VMs.

Let’s take the example of giving Internet connectivity to a bunch of VMs running on a dedicated VPC. In the context of a standard virtualization environment, it could be necessary to install a firewall, and to configure the network so that the VMs exit through it. This firewall would have the apparence of a VM, with its own OS. The footprint of that deployment would include the footprint of running an entire VM dedicated to handling firewalling and NATing.

However, within the context of an hypervisor where VMs and Pods can run next to each other, we can use lighter containers to provide these services. We can provision a container acting as the firewall, handling the NAT. The firewall can be handled through standard NetworkPolicies.

The amount of memory required for the execution of a virtual machine acting as a firewall has decreased from a few gigabytes of RAM to a few megabytes.

We could imagine deploying other services through pods, such as bastions, VPN or SFTPs. We effectively merge all the cloud native ecosystem into the world of VMs, which is traditionally painted as directly opposed to the philosophy of VMs.

Ease of Operation

Beyond facilitating seamless interactions between pods and virtual machines, Kubevirt also enables the extension of features available in deployments.

One interesting feature that we use for deploying Kubernetes on top of Kubevirt (KaaS or Kubernetes as a Service) are VirtualMachinePools. These VM pools are analogous to Kubernetes deployments in that they involve the definition of a VM model and the request for a number of replicas of this model.

In situations where additional nodes are required, the number of replicas can be augmented. On the other hand, during periods of reduced activity, the number of replicas can be diminished to align the number of virtual machines with actual demand.

Given its functional equivalence to Kubernetes, it is also possible to perform node drains. In the event of a failure of a node, virtual machines (VMs) will be automatically migrated to another node on the network, thereby ensuring the system’s high resilience.

Kubevirt facilitates the use of all features typically available in a cluster, for example, it allows:

- Services and CoreDNS to communicate between virtual machines and loadbalancing through domain names

- Node drains to live migrate VMs to other hypervisors while doing maintainance

- Affinities and taints to influence the placement of VMs

And many more! Pretty much anything you can do with pods can be transposed to VMs.

Making our VMs Persistent

Project Superphénix includes an entire subproject dedicated to moving away from NetApp. We decided to use Ceph and the Rook operator to transform Kubernetes in a storage orchestrator.

If you’re interested, you can read this paragraph and this dedicated article we have on how we handled storage.

We use the Ceph-CSI to provide block storage and ReadWriteMany volumes to our VMs. The feature we use the most is block storage, as it’s extremely close to how a real disk would operate.

Everything is always mounted using volumeMode: Block and Kubevirt handles presenting PVCs as a disk.

This part was suprisingly easy (if we forget about migrating the storage to Ceph), as the API to present disks to VM uses PersistentVolumeClaims, which are already used by any persistent pod on normal Kubernetes clusters.

The only things we had to extensively test were:

- the compatibility with Kubevirt’s live migration features

- the compatibility with Kubevirt’s snapshot/restore APIs

If your CSI doesn’t support those, you’ll miss out on the ability to move VMs from one node to another with no downtime. It would also be impossible to snapshot VMs or clone them.

As a CSP, those functionalities are absolutely needed. We need live migration to loadbalance our nodes (like the DRS on VMware), and to run scheduled maintainance on our hypervisors. We also need snapshots to help with setting up disaster recovery and backups.

Ceph supports those features very well and Kubevirt uses Ceph as its test CSI in the end to end tests. It makes this CSI an excellent choice considering it has first class support.

Benefits Of The CSI Integration

The standardization CSI employed by Kubernetes facilitates the management of multiple storage types and enables a fluid transition between them.

We can imagine the need for changing the storage medium or the storage system backing VMs during the project’s lifetime. Using Kubernetes and Kubevirt, we can easily transfer PVCs from one CSI to another. Such a feature is extremely useful to allow for decoupling the hypervision layer from the storage layer.

We plan on using this flexibility to help us migrate disks from NetApp to Ceph through the CSI API.

How We Do Snapshots and Clones

A fundamental component of VM management pertains to the capability to create a backup of the machine’s state. Kubevirt’s technology fulfills this need by integrating VM snapshot management with whatever CSI is installed on the cluster.

Kubevirt possesses the functionality to support cold copies and snapshots of the VM while it’s running.

Snapshots and clones are simply started by the creation of a custom resource of type VirtualMachineSnapshot or VirtualMachineClone. Kubevirt will then communicate with the QEMU agent present on the virtual machine (VM) to freeze processes and reduce input/output operations per second (IOPS), with the objective of avoiding data corruption during the copying process. Then, Kubevirt will launch the copy of the VM, including the storage, and finally unfreeze the VM so that it returns to normal operation.

Because Superphénix is an automated system, every customer resource have a pseudo-randomized name generated using an UUIDv5 and specific labels.

One issue we encountered with clones and restores is that they keep those labels intacts in the restored VM. We use labels for filtering and to automate billing/monitoring, and different VMs really cannot have the same IDs.

We fixed those issues by upstreaming some code to Kubevirt, making restores more predictable and allowing for overrides through JSON patches:

- feat(clones): support arbitrary patches on vmclones #14617

- feat(snapshots): allow for predictable snapshot restore pvcs #14723

VM disks and templates

Using Kubevirt and the Container Data Importer, we create virtual machine templates and golden images stored in Docker registries. We already know a lot about building and storing Docker images, including the versioning system that comes with it through tags.

That’s why we created our VM template registry using a standard Harbor instance. VMs can be initialized from a version of a Docker image (e.g ubuntu:20.04). We also setup Harbor mirroring between our different AZs (availability zones). The utilization of mirroring is intended to enhance the distribution of images and reduce latency when provisioning VMs in different datacenters.

The simplicity of manipulating disks in Kubevirt provides a multitude of possibilities, including the option of loading ephemeral disks into RAM. This allow one to start a VM from a fresh installation on each reboot for testing purposes. Kubevirt also offers the ability to add Secrets or ConfigMaps at VM startup, and to add a Cloudinit configuration.

What that means is that the creation of our VM, its persistence and its configuration is entirely defined using Kubernetes APIs.

Cloud Init

Let’s take a closer look at CloudInit. The primary benefit of a CloudInit configuration is its capacity to inject data during the initialization of the virtual machine. For example, the following options are provided:

- Configure the VM’s default user

- Configure Network

- Change hostname

- Add SSH keys

A CloudInit configuration is not limited to those options; however, the following are of particular interest. Every VM deployed on Superphénix embeds the QEMU agent and CloudInit to make autoconfiguration at boot easier.

SSH/VNC/Serial

In addition to the creation of virtual machines (VMs), the Kubevirt framework facilitates seamless access to these VMs.

There exist multiple possibilities for establishing a connection; the most prevalent of these is the Secure Shell (SSH) connection. As previously demonstrated in the CloudInit case, the process of adding SSH keys to virtual machines (VMs) can be automated.

In the event that Secure Shell (SSH) is unavailable, the second solution involves establishing a serial connection, that is, a direct connection to the virtual machine (VM) console. Kubevirt facilitates access via the command-line interface (CLI).

It is important to note, however, that multiple accesses to Serial are not possible, as each new connection will result in the disconnection of the previous one.

Kubevirt provides a method for connecting to virtual machines with a graphical interface, such as those running on Windows machines, via VNC.

We offer both serial and VNC on our web console, through a custom VNC proxy we built. It enforces permissions and traces actions from the users on the VM.

The Hardest Part: The Network

Kubevirt is pretty straightforward and was far from the most difficult part of the project.

But connecting VMs to the network fabric of Agora Calycé proved a bit more difficult.

Different alternatives were considered and tested and can be found in greater details in this article dedicated to the network of Superphénix.

We encourage you to read this article to understand a bit better the requirements a CSP needs to meet, and why the network layer is so challenging.

What’s important to note is that we heavily use the Kubevirt’s ability to create VMs with networks bound through Multus. This helps us connecting VMs to multiple different networks, and not just the default CNI of the cluster.

We use the managedtap binding of Kubevirt to delegate DHCP/DHCPv6 to the CNI, bypassing the Kubevirt layer. We gain more flexibiliy by offloading all the address assignment to our CNI, which is more capable than Kubevirt in that matter.

GitOps and Interactive Deployments

The Superphénix project offers two ways to operate the infrastructure and to deploy ressources:

- the web console, mainly destined for the customers

- GitOps, mainly destined for administrators and project managers (as they usually deploy resources on behalf of the users)

The entire project is architectured to reconcile both methods. What that means is that resources created using the web console can be reimported inside the GitOps, as the opposite is also true.

This is possible due to the way IDs are crafted in Superphénix, allowing for user-friendly ones to be used by the users in the Git, while preventing collisions.

You wouldn’t want two users to overwrite each others VMs or network because they both chose to call their resource “my-resource”, wouldn’t you? That’s why we use randomly generated UUIDv4 merged with the user-defined ID to generate UUIDv5 that are guaranteed to be collision-free.

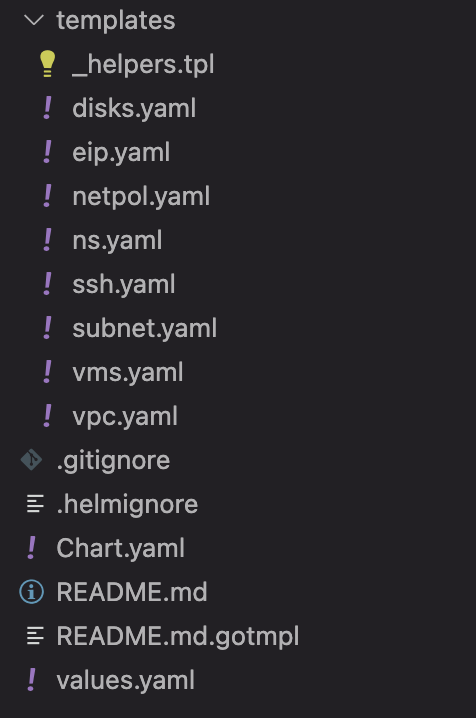

Helm Chart to deploy an entire project for our customers

And that’s how we can create Helm Charts written to deploy an entire customer’s environment with VMs, network, firewalling, disks and more.

We truly inherit the benefits of Kubernetes but apply it to an entire cloud service provider.

Conclusion

With Superphénix, we’ve successfully integrated VM virtualization into a Kubernetes-native workflow using KubeVirt. This lets us manage VMs just like containers, benefiting from Kubernetes features like scheduling, monitoring, storage orchestration, and GitOps.

By standardizing around Kubernetes, we simplify operations, reduce overhead, and gain flexibility in how we provision, migrate, and snapshot virtual machines. It’s a practical and efficient way to modernize CSP infrastructure without relying on traditional hypervisors.